King Jayasingha Warmadewa (960–975 AD): Strengthener of the Dynasty and Developer of Ancient Balinese Culture in Bedahulu

King Jayasingha Warmadewa contributed greatly to the political stability of Bali during his reign, according to preliminary historical research involving the examination of inscriptions, historical records, and academic literature. Through his support for religious and social activities, he strengthened the relationship between the kingdom, the community, and the Brahmin caste, creating a strong bond between the ruling class and the people. The arts, customs, and religious practices flourished under his leadership, and all of these became important components of Bali's cultural identity.

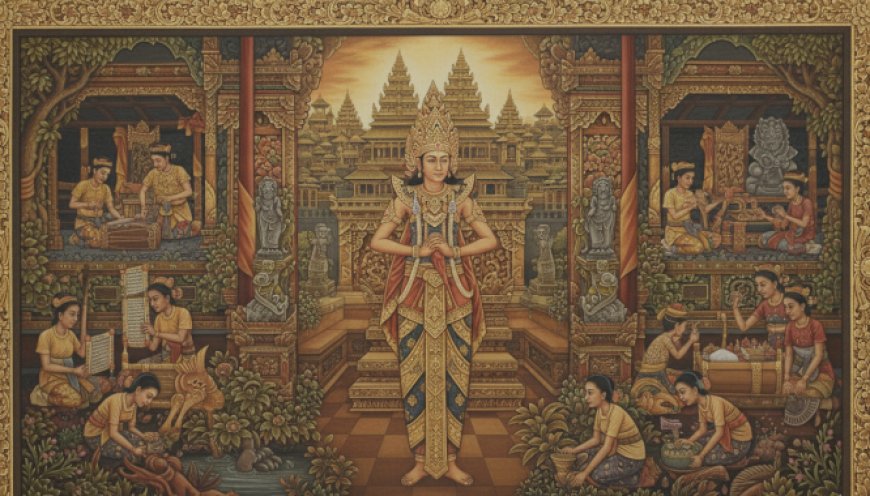

King Jayasingha was an important figure who helped develop the Warmadewa dynasty and ancient Balinese culture in the 10th century AD. Jayasingha, also known as Indrajayasingha, performed two strategic tasks: increasing the legitimacy of the dynasty and encouraging the growth of ancient Balinese culture in the center of ancient power. The Warmadewa dynasty was one of the most influential dynasties in ancient Balinese history. It lasted until the following century, although its historical records are not as extensive as those of Sri Kesari or King Udayana. Around 960–975 AD, King Jayasingha Warmadewa ruled in Bedahulu, the center of Balinese government at that time. His reign occurred before the emergence of great kings such as Udayana and Anak Wungsu, and after Sri Kesari Warmadewa. Studying Jayasingha is crucial to understanding the history of the dynasty, the structure of government, and the cultural progress of Ancient Bali, which shaped the identity of the Island of the Gods.

AI Illustration, An Inscription Mentioning King Jayasingha (Source: Private Collection)

This king issued only one inscription dated 882 Saka or 960 AD. The king's order was to repair the sacred Tirta Empul pool (now known as Pura Tirta Empul in Tampaksiring), which had been damaged by heavy water flow. The inscription, in the form of a stone pillar, indicates this action. The stone, inscribed with Balinese script, is still kept in the sacred place or temple, and is covered with white cloth during certain ceremonies. Most of the letters have been damaged and are no longer legible. The stone is brought to Tirta Empul every year to be worshipped. A French scholar named Dr. L.C. Damais later read the inscription on the stone. According to the scholar who researched this inscription, the king mentioned was named Jaya Singha Warmadewa and not Candra Bhaya Singha Warmadewa. In addition, the year was not 884, but 882 Caka.

The “Sekehe Barong” consider this place sacred, so they visit it every Galungan Day to perform rituals. Calculations show that the Tirtha Empul bathing place was 1,000 years old in 1960. The walls surrounding the Tirtha Empul water source are approximately 150 cm high. Black sand gushes from underground; water flows from various places. Many fish live in the lake where the water source is located. Water from the lake is channeled to the men's and women's bathing areas. The water flows from there and becomes a river called the Pakerisan River. In the story of Mayadenawa, it is said that the spring was created by Betara Indra from the inscription on the stone mentioned above. However, the story does not mention the origin or where the king built Tirtha Empul. In addition, many inscriptions are written on copper plates, as is commonly found. The Tirtha Empul inscription on the stone records the years 877–889. This indicates the reign of Jayasingha Warmadewa. Considering that the Tirtha Empul area is not far from Kintamani, it is said that King Singha Mandawa was related to Jayasingha Warmadewa, whose inscriptions were found in the Kintamani area. It is also possible that King Jayasingha Warmadewa himself built the Tirtha Empul bathing place.

As mentioned earlier, the king's name is often written incorrectly, such as Tawanendra, Taganendra, Sri Aji Nendra Warmadewa, and Ganendra Warmadewa. So, Indra Jaya Singha may also be Tawanendra. After the political crisis at the beginning of the Warmadewa Dynasty, Jayaasingha Warmadewa ruled during a period of stability. By implementing a system of sima, or freehold land, for the Brahmins, he strengthened the legitimacy of the dynasty. This political strategy aimed to gain the loyalty of the people and the elite. The structure of government used balanced the power of the king and the role of religious figures. Jayasingha sought to maintain stability by establishing good relations with the Bali Aga people in the interior. A strong socio-political network was formed by support for the Brahmins and priests. This ensured public support for the kingdom and strengthened the social structure of Ancient Bali. Jayasingha paid close attention to the construction and maintenance of sacred places such as temples and ritual sites. He supported religious and artistic activities, which helped the development of Balinese Hindu-Buddhist traditions. Under his rule, art, literature, and customs flourished, which form the basis of contemporary Balinese culture.

AI illustration, Cultural Heritage of King Jayasingha (source: personal collection)

Jayasingha Warmadewa left an important legacy of political stability and sustained cultural progress, even though he was not as popular as Sri Kesari or King Udayana. History and inscriptions show his reign until the time of Udayana and Anak Wungsu. King Jayasingha Warmadewa (960–975 AD) strengthened the Warmadewa Dynasty and developed Ancient Balinese culture. He maintained political stability, strengthened relations with the brahmins and the community, and encouraged the development of art, religion, and tradition through his planned leadership. His legacy contributed to Bali's glory for hundreds of years to come.

Bibliography (Main References)

Laksmi, Ni Ketut Puji Astiti. “Exploring the meaning of Drwyahaji and Buncanghaji based on data from ancient Balinese inscriptions.” Forum Arkeologi. Vol. 29. No. 2. Forum Arkeologi Bali, 2016.

Ekawana, I. G. P. (1983). Sambandha in several Balinese inscriptions. Berkala Arkeologi, 4(1), 21-36.

Mardika, I. M., Laksmi, A. R. S., & Suwendri, N. M. (2021). Preservation of Inscriptions at Dadia Pande Pangi Temple, Pikat Village, Dawan District, Klungkung. Postgraduated Community Service Journal, 2(1), 32-37.

Wahyuni, N. M. D. (2016). Hermits in Ancient Bali based on inscriptions from the 9th to 12th centuries AD. In Forum Arkeologi (Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 33-44).

Srijaya, I. W. (2024). The Existence of Dawan Village Based on Inscription Records Prasi A. AMERTA, 42(1), 69-80.